at Grand Gulf State Park

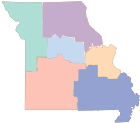

Missouri's Little Grand Canyon

Grand Gulf, often referred to as Missouri's "Little Grand Canyon," has a long history as a geologic curiosity. It is a spectacular sight and is a true chasm, deeper than it is wide.

Grand Gulf, often referred to as Missouri's "Little Grand Canyon," has a long history as a geologic curiosity. It is a spectacular sight and is a true chasm, deeper than it is wide.

To understand its origin, one must understand the geology of the area. The limestone and dolomite bedrock here are very soluble in the mildly acidic groundwater that percolates down from the surface. The water seeps into the fissures and fractures in the bedrock, eventually enlarging the cracks into caves.

Here at Grand Gulf is a cave system with a roof that collapsed an estimated 10,000 years ago. The result is a vertical-walled canyon about three-quarters of a mile long. Bussell Branch, a surface creek that drains about 28 square miles, empties into the chasm through a process called stream piracy. All of this water passes down the length of the chasm, under a 250-foot natural bridge (an uncollapsed remnant of the original cave) and back into the open canyon. Finally, at the lower end of the chasm, it enters the mouth of the remaining underground cave system. It travels 9 miles underground, and re-emerges at Mammoth Spring in Arkansas. Mammoth Spring flows as much as 9 million gallons of water per hour, part of it from the Grand Gulf.

The steep walls of the chasm are covered with herbaceous greenery, and from the upstream end down, the canyon gets rapidly deeper. The natural bridge, which spans the canyon at about its midpoint, is some 75 feet high at the upstream end, but the ceiling drops to about 10 feet high on the downstream side. The floor of the chasm is strewn with tumbled dolomite blocks that were once part of the cave roof, now collapsed.

The mouth of the portion of the cave that has not collapsed (at the downstream end of the chasm) is blocked only a short distance inside by mud and debris that allows the water from Bussell Branch to percolate through, but bars human access. In the early 1990s, a robot vehicle, equipped with a digging tool and remote camera, penetrated a significant distance into the cave. As a result of this reconnaissance, it was determined there is no feasible way through the massive blockage to gain access to the rest of the cave.

The mouth of the portion of the cave that has not collapsed (at the downstream end of the chasm) is blocked only a short distance inside by mud and debris that allows the water from Bussell Branch to percolate through, but bars human access. In the early 1990s, a robot vehicle, equipped with a digging tool and remote camera, penetrated a significant distance into the cave. As a result of this reconnaissance, it was determined there is no feasible way through the massive blockage to gain access to the rest of the cave.

Early explorers were able to enter the cave. Luella Agnes Owen, in her book "Cave Regions of the Ozarks and Black Hills" (1898), recounted her explorations in the Grand Gulf. After entering the cave at the downstream end of the chasm, "The ceiling dipped so we were not able to stand straight, and the guide said he had never gone farther; but to his surprise here was a light boat which I am ready to admit he displayed no eagerness to appropriate to his own use, and swimming about it, close to shore, were numerous, small, eyeless fish, pure white and perfectly fearless; the first I have ever seen, and little beauties," she wrote. Owen used the boat to explore the underground system for a considerable distance.

Access to the deeper portions of the cave remained possible until the 1920s when a severe storm washed many downed trees and other debris into the gulf, filling the cave. Today, heavy rains fill the gulf to depths exceeding 100 feet, and the water drains out slowly over a period of several weeks.

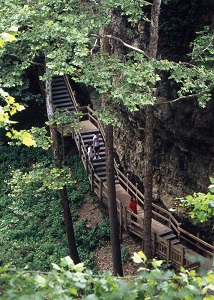

In 1971, Grand Gulf was designated a National Natural Landmark, and in 1984, the property became a Missouri state park through a lease agreement between the L-A-D Foundation and the Department of Natural Resources. The department has laid out trails and installed boardwalks at this day-use park, and there are many picnic sites scattered on the tree-shaded rim of the chasm.

See also: Grand Gulf Natural Area