at Sappington African American Cemetery State Historic Site

The Builders of Saline County

The Builders of Saline County

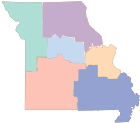

Saline County along with 16 other counties bordering or north of the Missouri River constituted Missouri’s “Little Dixie” region. The majority of immigrants to this region were from the upper southern states of Virginia, Tennessee and Kentucky. They brought their cultural, social, agricultural, architectural, political and economic practices, which included slavery. Hemp and tobacco became the major cash crops in the region during the 1830s. Hemp fiber was manufactured into rope, cloth and sails of ships. Both crops were labor intensive, so the number of enslaved people brought into the region increased significantly. A plantation system developed, mirroring the cotton plantations of the South.

Enslaved Black Americans represented 10% of Missouri’s population in the 1860 U.S. Census. However, the number of enslaved people in each “Little Dixie” county ranged from 20% to 50% of the total population. The Civil War disrupted the plantation system, and an ordinance of emancipation in January 1865 ended slavery in Missouri. Hemp was replaced by cheaper jute, imported from India, further eliminating the need for laborers. The plantations were broken up into smaller farms, often sold to newer immigrants arriving in the state. The “freedmen,” as the formerly enslaved were called, left their former plantations to create their own settlements or moved to larger towns.

In 1880, Black Americans comprised 51% of Arrow Rock’s total population. Historical accounts have been overlooked or often minimized their contributions to history. Black people built much of the infrastructure of Arrow Rock and improved the surrounding farmland. Their increasing presence kept Arrow Rock from sliding into complete economic oblivion following the Civil War. Thomas Rainey, an early historian of Arrow Rock, made this comment in 1914: “The forefathers of many of them helped to fence and clear the fields, open the roadways, and make Saline a pleasant place to live in. Although they now lie in nameless graves, we owe respect to their memory. They were also pioneers.” However, segregation persisted. Black individuals were forced to develop and maintain their own social, religious and educational institutions. Most communities in Missouri had designated cemeteries for Black burials, continuing the institution of segregation even after death.

In oral tradition passed down through his family, Emmanuel Banks, one of 24 enslaved workers held by Dr. John Sappington, shared that Sappington set aside 1 acre as a burial ground for his enslaved people before his death in 1856. The cemetery contains about 350 burials, many of whom are now unknown. Before the emancipation in 1865, there were probably no headstones, just simple wooden markers, if any at all.

In 1906, another half-acre was added to the cemetery as generations of Black Americans with links to the Arrow Rock community continued to use this cemetery. The last burial was of jazz and blues musician James C. Van Buren and took place in 2012. Other notable people buried at the site include Zack Bush, who helped stop the spread of an 1872 fire in Arrow Rock's business district; John Thomas Trigg, the first Black teacher in Arrow Rock to be born a free man; and members of the extended family of Emmanuel Banks.

Only about 75 grave markers remain today, but the eclectic variety of stones reflects the Black community’s economic and social status throughout its history as well as burial traditions. Some markers are simple concrete slabs with a name and date scratched in them. Others are simple flat markers on the ground. Only a very few are more ornate. The simplicity of this cemetery stands in stark contrast to the more ornate cemetery of the Sappington family. The open hilltop locale of the African American cemetery contributes to its overall aesthetic appeal.

The African American cemetery became part of Sappington Cemetery State Historic Site in 2014 and was recognized as a separate historic site in 2021. Along with these two facilities, Missouri State Parks also manages Jewell Cemetery State Historic Site, the final resting place of Missouri's 22nd governor, and Gov. Daniel Dunklin's Grave State Historic Site, the burial site of the state's fifth governor.