Iron Riders: The Story of the 25th Infantry Regiment Bicycle Corps

The Great Experiment

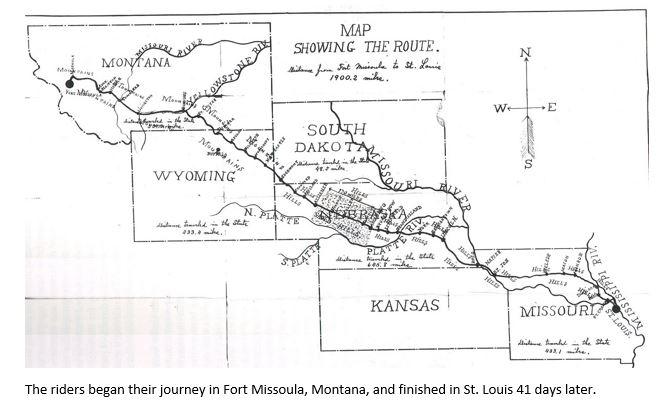

In 1897, the all-Black 25th Infantry Regiment Bicycle Corps embarked on an epic bicycle ride of more than 1,900 miles from Fort Missoula, Montana, to St. Louis, Missouri, as part of an experiment by the U.S. Army to determine the effectiveness of moving troops by bicycle. Called “The Great Experiment” in national newspapers, the journey took 41 days to complete. The route for the experiment closely followed the Northern Pacific and Burlington railroads through Montana, Wyoming, South Dakota, Nebraska and Missouri, and was chosen specifically to experience as many different conditions, climates and landscape formations as possible.

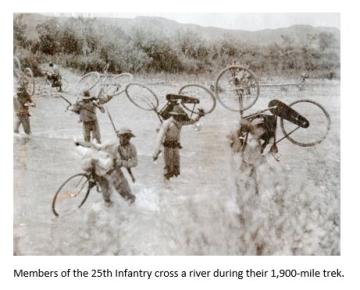

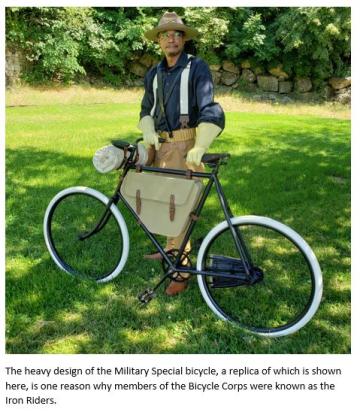

The 25th Infantry was one of six racially segregated units formed by the Army after the Civil War. Soldiers in these units were required to continuously prove themselves to their white counterparts because of the perception that Black soldiers were inferior in courage and ability. Members of the Bicycle Corps demonstrated the opposite was true. Nicknamed the Iron Riders because of the heavy one-speed bicycles they pedaled and for their iron-hard constitutions, the soldiers endured conditions along the route that would have daunted even the most avid of modern-day cyclists: severe weather events, extreme heat, food and water shortages, illness from alkali poisoning, and racism and hostility from local residents. Despite these challenges, the Iron Riders successfully reached their final destination in St. Louis on July 24 and were welcomed by a crowd of 1,000 cyclists who escorted them into Forest Park.

The Riders

Of the 23 men who embarked on the 1897 journey from Fort Missoula to St. Louis, 20 were enlisted Black soldiers (Buffalo Soldiers) who had volunteered for the trek. Three white men were also part of the expedition: 2nd Lt. James Moss, the 25th Infantry's commanding officer and a bicycling enthusiast; Dr. James Kennedy, an Army physician; and Edward Boos, a young newspaper reporter and fellow bicycling devotee. The enlisted men who were chosen for the ride ranged in age from 24 to 39, and all were in top physical condition. Five of the enlisted soldiers were veterans of previous, shorter bicycle trials, but some had never ridden bikes before. Because of the unique nature of the expedition, Army regulations required that each cyclist weigh no more than 140 pounds and be no taller than 5 feet, 8 inches. Moss had to receive special permission to allow participation by the handful of soldiers who exceeded these requirements. Below are the names and rank of the men who took part in the ride.

- Sgt. Mingo Sanders – Born in 1858 in Marion, South Carolina, Mingo Sanders was 39 when the ride took place, making him the oldest and most senior-ranking of the enlisted men. He joined the Army in 1881 and spent the entirety of his military career with the 25th Infantry. A year after the ride, Sgt. Sanders fought in Cuba during the Spanish-American War, alongside the Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry and Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. Following 25 years of outstanding military service, Sanders’ military career came to a premature end when President Roosevelt wrongfully dishonorably discharged him and 166 other members of the 25th Infantry, in a case of racial injustice known as the “Brownsville Affair.” Because he was dishonorably discharged, Sgt. Sanders was unable to receive a military pension. In 1972, he received a posthumous pardon from President Nixon after a new Army investigation found the accused men innocent.

- Lance Cpl. William Haynes – Born in 1866, just one year after the Civil War had ended, William Haynes enlisted in the Army in 1889 and was assigned to Fort Missoula, Montana, in 1894. Haynes was one of the original soldiers who participated in previous trial rides in 1896, including a 790-mile ride to Yellowstone National Park and back. Military records show he rose to the rank of first sergeant during his career, due in large part to being consistently described as having a “very good” or “excellent” character. A year after his final discharge in 1909, tragedy struck Haynes and his wife Zada, when their youngest son, Henry, drowned in the Spokane River in Washington. Young Henry was buried at Fort George Wright in Spokane, Washington, where Haynes was posted at the time of the tragedy. Families of active-duty soldiers were allowed to be buried in the fort’s integrated cemetery, as were veterans of all branches of the military, regardless of race.

- Lance Cpl. Abram Martin – Abram Martin enlisted with the Army at Fort Randall, South Dakota, in 1881 when he was just 21. Born in 1861 in Charleston, South Carolina, just as the Civil War was beginning, the 36-year old Martin was one of two squad leaders during the 1897 ride, the other being Lance Cpl. William Haynes. During his 27-year military career, in addition to riding with the Bicycle Corps, Martin also served in the Philippine-American War that occurred from 1899 to 1903. At the age of 47, Martin officially retired from the Army as a first sergeant and, similar to Haynes, was consistently rated as having “very good” or “excellent” character in his military records.

- Musician Elias Johnson – Born in Washington, D.C., in 1870, Johnson served the 25th Infantry from 1891 to 1899, which meant that he also served during the Spanish-American War in Cuba. In a report to the adjutant general of the U.S. Army in September of 1897, 2nd Lt. James Moss listed Elias Johnson as the musician for the Bicycle Corps. The term “musician” was used to indicate the company bugler. Army musicians signaled the daily calls that regulated post life and sounded commands on the battlefield. Johnson continued to serve as a musician until his final discharge from Fort Bayard in New Mexico in 1899. He passed away on Aug. 9, 1938, just a week shy of his 68th birthday, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

- Pvt. Travis Bridges – Little is known about Travis Bridge’s personal and military life. Military records show that, after 13 years of U.S. Army service and only four months after the 1897 bicycle journey, Bridge’s military career came to an abrupt halt with a dishonorable discharge. Following his discharge, no records of Bridges can be located. Interestingly, he had something in common with Elias Johnson. While serving with the 25th at Fort Buford, North Dakota, he too was listed as a musician serving as the company bugler. Additionally, while serving with the 25th Infantry at Fort Missoula, but before joining the Bicycle Corps, he was a member of the 25th Infantry military band, which provided entertainment to maintain soldier morale as well as performed at community concerts and parades.

- Pvt. Francis Button – Born in Prince William County, Virginia, in 1874, Francis Button enlisted with the Army in 1890 at the age of 21 and was assigned to the 9th Cavalry. His experience with the cavalry served him well when he reenlisted in 1895, this time with the 25th Infantry; his 1898 discharge papers from the 9th Cavalry indicated that he was a “Saddler Excellent.” The duties of a U.S. Army saddler involved making or repairing anything made of leather. This included repairs to saddles, bridles, halters, harnesses and other leather equipment associated with horses and mules, as well as repairs to leather belts, holsters, rifle slings and boots for the soldiers.

- Pvt. John H. Cook – John H. Cook was 22 years old when he first enlisted in 1894 in Pennsylvania. Assigned to the 25th Infantry during his 12-year military career, Cook also served in the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars. He rose to the rank of corporal before being unfairly dishonorably discharged in the same manner as Sgt. Mingo Sanders, during the Brownsville Affair. In 1906, the 25th Infantry was stationed at Fort Brown near Brownsville, Texas. The townspeople of Brownsville resented the presence of the Black soldiers at the fort, so when a shooting occurred in town that killed a white bartender and wounded a white police officer, the townspeople accused the soldiers of the shooting, and historical research suggests they might have even planted evidence to support their accusations. Although white commanding officers insisted the soldiers had been in their barracks at the fort during the shooting incident, the accounts of the townspeople were believed, which resulted in the dishonorable discharge of the 167 men of the 25th Infantry stationed at Fort Brown. A new military investigation in 1972 exonerated the soldiers, most of whom were deceased at that point, and restored their records to show honorable discharges.

- Pvt. Hiram L.B. Dingman – U.S. census records provide conflicting information regarding the birth details of Hiram L.B. Dingman, with some records indicating that he was born around 1865 or 1868 in either New Jersey or in Canada. Other census records indicate that it was actually Dingman’s father who was Canadian. Dingman enlisted with the Army in 1887 at the age of 22 and served for 12 years. His military records indicate that he had risen to the rank of sergeant with an “excellent” character by the time of his discharge in 1899.

- Pvt. John Findley – A Missouri native, John Findley’s Army enlistment records show he was born in Carrollton, Missouri, in 1874. Findley served as the corps’ bicycle mechanic and was reported as being a “crack rider and boss repairer” by a St. Louis Post-Dispatch newspaper article. When a bicycle would break down, he would switch bicycles with the other rider and begin making the repairs. Once the repairs were complete, he would ride the repaired bicycle until he caught up to the corps. Findley gained his expertise as a bicycle mechanic from four years working for the Imperial Bicycle Works of Chicago, and his skill at both repair and riding were mentioned by Moss in his notes.

- Pvt. Elwood “Edward” Forman – Although little is known about Elwood Forman’s life before the Army, military records indicate that he played on the 25th Infantry’s baseball team, participated in the 1896 trial rides, and rose to the rank of corporal before his military career was prematurely ended with his death. He served in the 25th Infantry for three enlistment periods, including during the Spanish-American War in 1898, where he sustained an injury to his left arm during the fighting. Forman died on April 22, 1901, of acute pulmonary tuberculosis while serving in the Philippines. On July 13, 1901, Elwood was interred in the Philadelphia National Cemetery.

- Pvt. Frank L. Johnson – According to his enlistment records, Frank L. Johnson first enlisted and was assigned to the 25th Infantry in 1895 at the age of 22. Johnson, who hailed from Connecticut, was one of only five men who participated in the previous trial rides in 1896. The other four included Elwood Forman, William Haynes, John Findley and William Proctor. Even after he was honorably discharged from the Army in 1899, Johnson continued in military service, enlisting in the New York National Guard in 1916.

- Pvt. Sam Johnson – Very little is known about the life of Sam Johnson, apart from the limited information available in the 1880 U.S. census and his records with the U.S. Army. Johnson enlisted at the age of 21 in Illinois. After four years of service and barely three months into his third reenlistment, Johnson deserted on May 13, 1899. Because “Sam Johnson” is a common name, it is difficult to research further details about his life and the reason for his desertion.

- Pvt. Eugene Jones – Born in Indiana in 1866, Eugene Jones first enlisted with the 25th Infantry in 1889 at the age of 21. During each of three subsequent discharges, he was listed as either of “good” or “excellent” character, and had reached the rank of corporal by 1898. These character descriptions make puzzling the following report from Moss to the adjutant general in September 1897: “Of the 20 soldiers who left Fort Missoula, 19 reached St. Louis in good health. Pvt. Eugene Jones, Co. H, who claimed to be ill and unable to ride, was sent back to Fort Missoula from St. Joe, Missouri. I have every reason to believe this soldier was merely feigning illness, thinking I would send him the rest of the way to St. Louis by rail. As he had given me trouble on several occasions I thought it would be best for the public service to send him back to his station.” Without Jones’ account, however, we can’t know what prompted his behavior on the ride or what was behind the cryptic “char. not obtainable” statement in his 1902 discharge paperwork.

- Pvt. William B. Proctor – William B. Proctor had a long and illustrious 30-year military career, which began in 1892 in Washington, D.C. During his time in the military, Proctor made the 1,900-mile bike ride with the 25th Infantry; saw action in Cuba during the Spanish-American War; and served in Hawaii during World War I, where he earned a Victory Medal. In 1922, Proctor retired from the military as a second lieutenant, but continued to serve by playing a prominent role in his community until his death in 1964 at the age of 91. His son, William B. Proctor, Jr., followed in his military footsteps, becoming a major in the U.S. Army.

- Pvt. Samuel A. Reid – Born in Charlotte, North Carolina, in 1873, Samuel A. Reid enlisted with the Army when he was 20 years old. He was assigned to the 25th Infantry the entirety of his career, and served in the Philippine-American War in Botolan and Zambales Luzon, Philippines. He had risen to the rank of sergeant by his final discharge in 1913. Following his discharge, Reid and his wife, Bessie, were listed in the 1920 census as teachers at a high school in Concord, North Carolina. By the 1930 census, the couple were living at Immanuel College in Greensboro, North Carolina, with their adopted son, Buford. Bessie served as matron, and Reid served as the supervisor of male students. Immanuel College was a residential high school, junior college and theological seminary for Black Americans operated by the Missouri Synod of the Lutheran Church from 1903 to 1961.

- Pvt. Richard Rout – While the 1897 bicycle ride was well documented in Moss’ reports and journals, very little of what the enlisted men felt and thought was recorded, with the rare exception of Pvt. Richard Rout. An interview of Rout by a Globe-Democrat reporter was recounted in an article in the Daily Iowa Capital, dated Aug. 18, 1897. During the interview, Rout stated that “they had encountered numerous obstacles on the way” and that “their greatest difficulty was experienced in passing through the sand hills of Nebraska,” where they had to “walk through 185 miles of sand, pushing their bicycles before them, the thermometer registering 110 degrees in the shade.” It is a reflection of the times that the voices of the riders weren’t heard in the many newspaper articles that reported on the status of their journey. It is fortunate to have this sole example, which gives a glimpse of some of the hardships the riders had to overcome.

- Pvt. George Scott – George Scott was born around 1870 in Columbus, Ohio, and first enlisted with the Army in 1894 in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, at the age of 24. Apart from his 11-year military career, very little is known about the life of George Scott. Research suggests that he died from pulmonary tuberculosis at the age of 39 and donated his body to the Ohio State University’s College of Medicine and Pathology.

- Pvt. Sam Williamson – Born in 1873 in Fayette County, Tennessee, Pvt. Sam Williamson was the younger brother of Pvt. William Williamson, also a member of the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps. Both brothers enlisted together in 1895 in Louisville, Kentucky, and were assigned to the 25th Infantry. The brothers also fought together in Cuba during the Spanish-American War in 1898 and reenlisted together in St. Louis later that year. After that, their military careers diverged, with the younger Williamson brother being sent to the Philippines during the Philippine-American War, where he was discharged in 1901 as a private with “very good” character.

- Pvt. William Williamson – Two years older than his brother Sam, Pvt. William Williamson, or “Willie,” rose to the rank of corporal with “excellent” character when he was discharged in Santiago, Cuba, in 1898. After reenlisting with his brother in St. Louis in November of 1898, William Williamson was assigned to Fort Sam Houston, where he had his final discharge in 1899 as a private with “very good” character.

- Pvt. John H. Wilson – Born in 1865 in Sprout Springs, Virginia, John H. Wilson was 22 at his first enlistment, which occurred in 1887 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Unlike several other members of the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps, Pvt. Wilson was not initially assigned to the 25th Infantry. Instead, his first two enlistments were spent with the 9th Cavalry. It wasn’t until his third and final reenlistment in Lynchburg, Virginia, in 1895 that he was assigned to the 25th. One year after the ride, he was discharged from Fort Missoula as a private with a “good” character.

- 2nd Lt. James A. Moss – After graduating last in his class from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1894, Moss was assigned to Fort Missoula, where he was put in command of the 25th Infantry. Graduates who ranked at the head of the class were given the pick of assignments, whereas graduates who ranked lower were assigned to less sought-after posts. At the time of Moss’ assignment, Fort Missoula was on the periphery of the western frontier and not considered the most desirable of posts. Black soldiers, like those of the 25th Infantry, were more likely to be assigned to remote outposts, such as Fort Missoula, because the Army felt this would help prevent racial violence from white soldiers and townspeople who discriminated against Black soldiers. As a white southerner born in Louisiana, Moss was a product of his time and often used stereotypical language in his reports and journals when describing the soldiers in his command. At the same time, he also wrote that the soldiers were “… about as fine a looking and well-disciplined lot as could be found anywhere in the United States Army,” demonstrating the respect he must have felt for the soldiers despite the racial stereotypes of the time. After the 1897 bicycle ride, Moss would go on to have a successful 30-year military career with the Army, serving in the Spanish-American War, where he was recommended for brevet captain for “gallant and meritorious conduct” at the battle of El Caney, Cuba; serving as acting superintendent of Sequoia and Grant national parks; serving in the Philippines in 1900-1903, where he won a Silver Star; and serving in France during World War I. In addition, Moss authored several books both before and after his retirement from the Army in 1922.

- 1st Lt. James M. Kennedy – James M. Kennedy was the assistant post surgeon for Fort Missoula and was assigned to accompany the Bicycle Corps on the 1897 bicycle trek, to deal with injuries or illnesses the riders might incur during the journey. Moss reported that Kennedy was “an enthusiastic wheelman,” contrary to a July 1897 article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that claimed he had to learn to ride a bike within a week in order to ready himself for the journey. During a four-day period in July while the riders were in Nebraska, Kennedy had to assume command of the Corps for Moss, who was recuperating from alkali poisoning as a result of drinking contaminated water. In addition to participating in the historic bike ride, Kennedy had a long and illustrious career with the Army, including serving as the assistant surgeon general and commander of Walter Reed Hospital, and rising to the rank of brigadier general before retiring at the age of 64.

- Edward H. Boos – Only 20 when he rode with the corps in 1897, Edward “Eddie” Boos was a freelance journalist who wrote for newspapers in the Missoula area. A fellow cycling enthusiast, Boos was invited to join the ride by Moss to provide detailed accounts of the journey for the Daily Missoulian. Many of Boos’ articles were picked up and published in newspapers along the route, as well as reprinted in national and international newspapers. After the bicycle expedition, Boos began photo-documenting the people and landscapes in the Missoula and Flathead valleys, with particular emphasis on the lifestyle, possessions and landscapes of tribal members living on the Flathead Reservation. His extensive photograph collection is now housed with the Mansfield Library, University of Montana.

The Bicycle and Gear

In order for the members of the 25th Infantry Bicycle Corps to be successful on their 1,900-mile journey, they needed bicycles that could withstand the variable terrain through which they would ride. A.G. Spalding & Bros., which would eventually become the major manufacturer of sporting goods known as Spalding, agreed to donate specially designed bicycles for the riders. The Military Special, as it was known, had a sturdier front fork that absorbed the bumps of the rough roads; an ergonomically designed seat, the Christy saddle, for comfort on long rides; protective coverings for the chains to prevent damage from dust, mud and rocks; diamond-shaped frame cases that fit in the space between the top, seat and down tubes; and metal tire rims.

With these modifications, the steel-frame bikes were very heavy, weighing 32 pounds. Fully loaded with each rider’s gear, the average weight of the packed bicycles was 60 pounds. In a report to the adjutant general, Moss stated that, “Every soldier carried one blanket, one shelter-tent half and poles, one yard mosquito netting, one bicycle wiping cloth, one handkerchief, one pair drawers, one undershirt, two pair socks, one knife, fork, spoon, cup, tin plate, toilet paper, tooth brush and powder. Every other man carried one towel and one cake soap.” The diamond-shaped frame cases carried each soldier’s rations, which included salt, pepper, baking powder, flour, dry beans, ground coffee, sugar, bacon, hard bread, canned beef and baked beans. When in camp, the frame cases could be taken apart and used as frying and baking pans. Each soldier also carried a 10-pound rifle and wore a cartridge belt with 50 rounds of ammunition.

The Route

Each of the five states through which the soldiers rode – Montana, Wyoming, South Dakota, Nebraska and Missouri – presented its own unique set of challenges. In Montana, heavy rain at the beginning of the trek turned the road to muddy “gumbo,” making it so impassable that the soldiers chose instead to ride on the Northern Pacific Railroad tracks, having to endure endless jarring from riding over the ties. At the Continental Divide, blowing sleet and snow reduced forward visibility to less than 20 feet, and the freezing temperatures forced the cyclists to make frequent stops to warm their hands and ears. In both Montana and Wyoming, the soldiers were forced to wade through the Little Big Horn River multiple times, carrying their bikes on their shoulders. Moss reported that the journey through northeastern Wyoming and southeastern South Dakota “was very dreary – the landscape was a monotonous series of hills, with now and then an alkali flat, while the water was abominable.” Boos reported riding over “a great prickly pear prairie,” although no one sustained a tire puncture. In Nebraska, the corps experienced sandy roads, some where the sand was so deep that the riders were forced to dismount and push their bicycles along and, in some places, ride the railroad tracks again. The riders also suffered the ill effects from drinking alkali water, as well as the excessive July heat.

On July 16, 1897, the cyclists were ferried across the Missouri River at Rulo, Nebraska, and made their way into Missouri. Although Missouri was the last leg of their journey, it continued to be an arduous trip. An article in the Kansas City Journal reported: “The roads across Missouri were bad and hilly and with the exception of a few gravel roads, were the worst on the entire trip. When away from the railroad the people were inhospitable. In one instance water sufficient for cooking being refused, and no reliable information regarding the roads could be gained. The heat for the last three days of the trip was severe and hard on the men.”

Locations in Missouri where the riders camped included Napier (near present-day Big Lake State Park), St. Joseph, Hamilton, Laclede, Macon, a location near Monroe City, Louisiana, and a location near St. Peters. Local newspapers reported the passage of the soldiers. The Farmers Advocate in Hamilton recounted the following: “Somewhat of a stir was created Sunday afternoon in town when a detachment of the United States regular army came through on bicycles. United States regulars seldom visit Hamilton and a sight of a number of them fully armed and equipped would have been sufficient in itself to cause a commotion. To see them mounted on wheels was, however, an unusually strange sight.” An article in the St. Louis Star mentioned, “The best riding on the trip was from Louisiana to Eolia in Pike County.” There was a historical reason for this. According to a 1902 article in Good Roads magazine, Pike County had some of the best and well-maintained toll roads in Missouri at that time. The revenue from the tolls enabled the county to keep the roads in better repair than country roads elsewhere.

Moss recounted that on the last day of their ride, the riders had to endure a heavy rainstorm, broiling heat, thick river-bottom mud and a rough railroad track before reaching their final destination, St. Louis, at 5:30 p.m. July 24, 1897, “… and thus it came to pass that the Twenty-fifth United States Infantry Bicycle Corps made the greatest march known of in military history.” As the soldiers rode into St. Louis, newspapers reported that they were welcomed by a crowd of 1,000 cyclists and a squad of mounted police, who escorted them through a mass of cheering spectators into Forest Park. An article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch on July 25, 1897, summarized the Great Experiment with these words: “The ride of Lieut. Moss and his men is a feat of world-wide interest. Military cycling has been the rage in Germany and France, but nothing approaching this 2,200-mile [sic] journey has been accomplished.”

The 125th Anniversary Commemoration

The year 2022 marks the 125th anniversary of the 25th Infantry Regiment Bicycle Corps’ incredible journey. To commemorate the anniversary, Missouri State Parks partnered with Lincoln University of Missouri, the Greater Los Angeles Area Chapter of the 9th and 10th Horse Cavalry Association, and the Missouri Parks Association to host a series of events that told the little-known story of these soldiers and their extraordinary accomplishments. The locations of these events followed the historic route the soldiers rode through northern Missouri, and included:

- Big Lake State Park on Sunday, July 17

- Gen. John J. Pershing Boyhood Home State Historic Site on Tuesday, July 19

- St. Jude’s Square in Monroe City on Thursday, July 21

- The Missouri History Museum in Forest Park in St. Louis on Sunday, July 24

- And, The Bruce R. Watkins Cultural Heritage Center in Kansas City on Saturday, Oct. 8

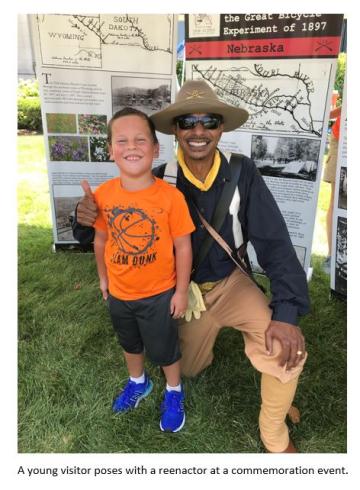

Each of these locations featured Buffalo Soldier reenactors, exhibits about the soldiers and their route, a replica of the bicycle the solders rode, activities for kids, period music, food, and a chance to visit with Erick Cedeño, the “Bicycle Nomad,” as he reenacted the 1,900-mile ride.

Merchandise

Missouri State Parks has Iron Riders merchandise available for purchase online. To view these items, visit the Missouri State Parks online store and search for "Iron Riders" or "Buffalo Soldiers."