at Annie and Abel Van Meter State Park

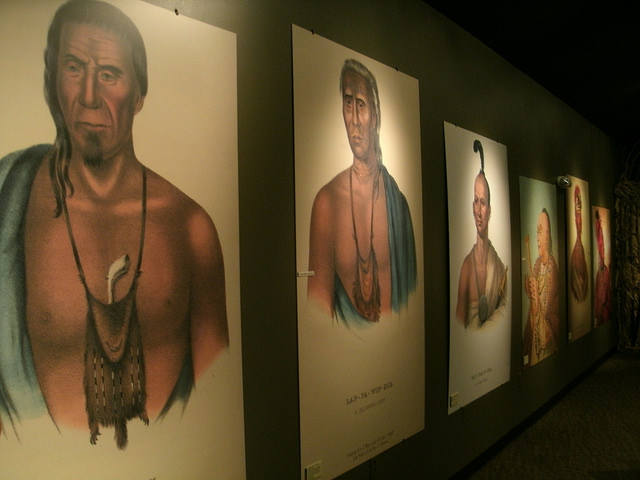

The Missouri Indians first came to the attention of Europeans through the account left from the Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette expedition in 1673. On the Marquette map, they are referred to as the "Oumessourit." This is the Illinois name for them, and can be translated as the "people of the dugout canoes." It is not what the Missouri called themselves, but the name would remain.

The Missouri Indians first came to the attention of Europeans through the account left from the Louis Jolliet and Father Jacques Marquette expedition in 1673. On the Marquette map, they are referred to as the "Oumessourit." This is the Illinois name for them, and can be translated as the "people of the dugout canoes." It is not what the Missouri called themselves, but the name would remain.

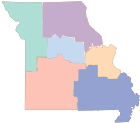

The Missouri were not newcomers to the area. While the Osage and Illinois had been pushed westward from the east after Europeans started settling the East Coast, the Missouri had been here for centuries. The earliest Oneota (ancestral Missouri) site in the area dates from A.D. 1250, and the Missouri Indian village (the Utz site) dates from as early as A.D. 1450.

The Missouri were typical prairie dwellers. They lived in large rush mat-covered houses with from 15-25 people in each. These longhouses were fairly widely spaced across the village, which contained approximately 5,000 people at first European contact. The people grew corn, beans and squash in small agricultural plots, probably in the bottomlands. The crops were planted in the spring, and the people stayed in the village through the early stages of the crops. In June, they left on the summer hunt, principally seeking bison. In August, they returned to harvest the crops. While most remained for the rest of the year, the men often left on other hunting trips through the winter.

The Old Fort, an irregular, double-ditched earthwork located in the park, was built by the ancestral Missouri Indians (Oneota). Archaeological investigations have not yet revealed the nature and purpose of this interesting man-made feature of the landscape.

Because the Missouri were the first group encountered on the Missouri River, they were visited early by the French. Probably the first direct contact with Europeans came in 1680 or 1681 when two traders were captured by the Missouri and taken to their village. The first recorded encounter was in 1682 when French explorer Sieur de La Salle, Robert Cavelier, was on his way south to the mouth of the Mississippi River. His party came upon a group of Tamaroa (Illinois Indians) and some Missouri on their way to conduct a raid on the Osage Indians.

About 1715, the Little Osage Indians moved from western Missouri and established a village near the Missouri to have greater access to fur traders. The Missouri often stopped traders from going upriver to obtain guns, lead and other items from them. Following the Big Osage and Little Osage, the Missouri contributed significantly to the fur trade in St. Louis.

There are a number of accounts from the early part of the 18th century, with many centering around the construction of Fort Orleans by Etienne Veniard de Bourgmond across the river from the Missouri Indian village in 1721. De Bourgmond's account of his visit to the Kansa Indians the following year illustrates that the Missouri Indians had already been heavily affected by European diseases. When de Bourgmond came down with a fever, most of the people with him fled the expedition. Fort Orleans was abandoned in 1728, and it appears that shortly thereafter, the remaining Missouri moved to the Late Missouri Indian village near the Little Osage Indians.

Disease and warfare with other tribes took their toll on the population. By 1758, there were only about 750 Missouri remaining. Warfare with the Sac and Fox and Ioway in the late 18th century forced the Little Osage and Missouri to abandon the area. Most of the surviving Missouri joined with the Otoes in Nebraska.

In 1804, the Meriwether Lewis and William Clark Expedition passed the area and noted the location of the Late Missouri Indian village and the village of the Little Osage. Farther upriver, the first Indians they met were the remainder of the Missouri living with the Otoes. They estimated that there were 300 Missouri there at that time. By 1829, there were only 80 Missouri alive; 40 in 1882; and the last full-blooded Missouri Indian died about 1908. However, some members of the Otoe-Missouria Nation of Oklahoma continue to count their linage as Missouri.