at Mastodon State Historic Site

The important archaeological and paleontological site preserved today in Mastodon State Historic Site had its origins in prehistoric Missouri. The glaciers to the north were slowly melting as the Earth warmed at the end of the ice age that occurred from 35,000 to 10,000 years ago. Animals such as giant ground sloths, peccaries and hairy elephantlike mastodons roamed the Midwest. Paleontologists theorize that the area was once swampy and contained mineral springs. Animals that came to the springs may have become trapped in the mud, which helped preserve their bones. Early American Indians also had reached present-day Missouri by at least 12,000 years ago. For a brief period at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, the lives of humans and mastodons intertwined.

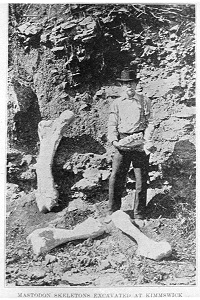

The first recorded report of bones of mastodons and other now-extinct animals in the vicinity of the town of Kimmswick was in the early 1800s. Albert C. Koch, Ph.D., private entrepreneur and a St. Louis museum owner, investigated a report of bones weathering out of the banks along Rock Creek and conducted excavations in 1839. Thinking he had discovered a new animal, he named his find the Missouri Leviathan and exhibited it in the United States and Europe. Richard Owen, a comparative anatomist at the British Museum in London, convinced Koch the skeleton was not a new animal but an American mastodon.

At the turn of the 20th century, nationwide interest in the site was revived when amateur St. Louis paleontologist C.W. Beehler excavated several skulls, jaws, teeth, tusk and other fossils in the area. Railroad tours from St. Louis brought many lay and professional visitors, particularly during the 1904 World’s Fair, to visit Beehler’s wood shack museum near the bone bed. Beehler’s excavations were not well documented so the recovery of stone artifacts in the deposit was not initially accepted as showing the presence of humans during the Pleistocene epoch.

At the turn of the 20th century, nationwide interest in the site was revived when amateur St. Louis paleontologist C.W. Beehler excavated several skulls, jaws, teeth, tusk and other fossils in the area. Railroad tours from St. Louis brought many lay and professional visitors, particularly during the 1904 World’s Fair, to visit Beehler’s wood shack museum near the bone bed. Beehler’s excavations were not well documented so the recovery of stone artifacts in the deposit was not initially accepted as showing the presence of humans during the Pleistocene epoch.

Unfortunately, many of the remains from the Kimmswick Bone Bed disappeared or were destroyed throughout the years. In addition to many non-scientific digs where people gave away or sold bones and tusks, there was a quarry operation on the site from the 1870s through the 1930s that destroyed many of the ice age animal remains.

From 1940-1942, excavations by archaeologist Robert McCormick Adams from the St. Louis Academy of Science were sponsored by the Works Progress Administration. He recovered additional fossils but few artifacts.

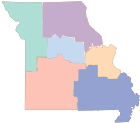

Construction of Interstate 55 in the 1970s renewed public concern for the site. The Mastodon Park Committee organized a movement to save the site from future destruction. Through the efforts of the committee, local legislators, private individuals, corporations and local school children, and with the help of a federal grant, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources was able to purchase the 418 acres containing the bone bed in 1976 and add it to the Missouri state park system.

Missouri State Parks sponsored excavations of the bone bed in 1979, 1980 and 1984. In 1979, paleontologist Russell W. Graham, Ph.D., of the Illinois State Museum provided the first solid evidence of the coexistence of humans and mastodons when a stone “Clovis” type projectile point was found in association with mastodon bones. This was the first site in eastern North America where this association was conclusively demonstrated.

The Kimmswick Bone Bed is important in the history of archaeological discovery as well as a rare example of a stratified ice age Paleo-Indian Clovis culture hunting activity. It is one of the oldest known archaeological sites in Missouri (over 10,000 years ago). Presently, the Clovis culture is the earliest well-documented Native American occupation for North America. Due to its archaeological and paleontological significance, the Kimmswick Bone Bed was placed in the National Register of Historic Places on April 14, 1987.

There are currently no excavations at the site, and remnants of the bone bed are safely buried. Visitors may take Wildflower Trail, which begins near the museum, to the site where the bones and artifacts were found.